Almost two years ago I stumbled on the National Capital Commission’s plan to include a narrow, completely unprotected bike lane in the redesign of the Alexandria Bridge. In response I wrote a post explaining how this design could easily be made a great deal safer for cyclists, and more ecologically sound.

My proposal for safe active transit in downtown Ottawa runs counter to the long-cherished ideal of a national capital held together by parkways. In such a vision, urban cyclists and pedestrians are merely an impediment to the experience of driving around distracted by tulips, grass, historic monuments, and the occasional splash of colourful fabric.

View of the Proposed Confederation Boulevard-Sussex Drive Rehabilitation, King Edward to St. Patrick.

This vision of downtown Ottawa as a touring motorist’s paradise is baked into the NCC’s 1959 founding document, the National Capital Act, which refers to “any street, road, lane, thoroughfare or driveway” as a highway—i.e. a place for cars. The National Capital Act served to implement the 1950 Gréber Plan for the city that we now know call Autowa. The Gréber plan is a hefty 400-page tome, but one can get the basic idea from the remarkable ten-minute film Capital Plan, available in full on the NFB website.

At the 6:45 mark Capital Plan portrays a scene of Ottawa commuters jammed onto wide rush-hour sidewalks and streets.

By 21st century planning standards this is a utopia of walkability and ready access to public transit. But back in the Golden Age of Motordom, commuting by means other than private automobile was considered outmoded and déclassé. A voiceover to that segment explains that this street jammed with people and streetcars creates a terrible predicament for the poor motorists, who get agitated “when the traffic moves at a snail’s pace.”

Here as in so many cities, the solution was to rip out the streetcar tracks, narrow the sidewalks, and build a network of high-speed car sewers throughout the city. A cartoon version of the coming urban highway network is depicted in light blue at 9:08 in the 1949 film:

(In the film it’s rather cute, with little cars moving along all the nice new roads.)

Here’s the same highway network as proposed in Plate XXVI of the 1950 Gréber Plan:

In the Gréber plan cycling and walking are not recognized as modes of urban transit. The only mention of these activities (two references to cycling, and three to walking) view them both as leisure activities reserved for rural or suburban recreation areas.

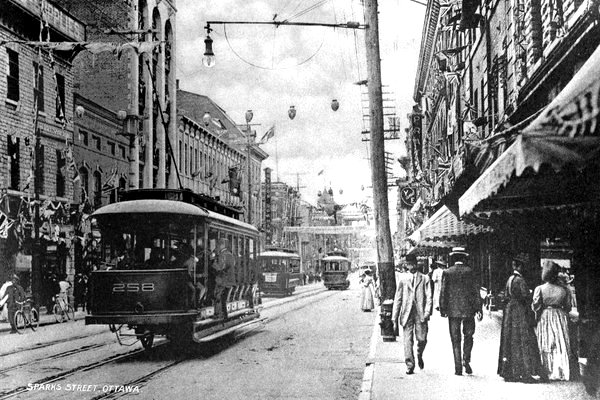

Early photographs of Ottawa likewise tell the story of the triumph of motordom. Bicycles are a regular presence in the early decades of the 1900s, but they largely disappear from the picture once the streetcars are replaced by high-speed automobiles, and the roadsides by parking.

In our own day urban planners realize that if you build streets for cars you will get more cars, and therefore more congestion. This well-proven principle is variously called the law of induced demand, law of latent demand, law of induced traffic, and law of congestion. Increased traffic has had a devastating effect on public health, due to the decrease in exercise and the rise in pollution and collisions.

We’ve known about the downsides of motordom for a very long time. Countries like Denmark and the Netherlands began reversing the effects of auto-centric planning a generation ago, and they have since become leaders in sustainable active transit infrastructure. Meanwhile in Canada’s capital, many factors, including the tireless work of the petroleum and auto industry lobbyists who helped remove the streetcars, have conspired to keep us mired in the motordom mentality.

In Ottawa, as I’ve suggested, the bureaucratic impediments enshrined in the National Capital Act present yet another obstacle to progress away from car-centric planning. It’s disheartening to realize that in 2016 the NCC is choosing between two proposals for a massive theme park—one complete with a motoring shrine full of bogusly-provenanced antique cars and a showroom for street racers—to be built along the Centretown waterfront. This is the NCC’s best idea for reviving Lebreton Flats, which was a vibrant working-class neighbourhood until it was expropriated and recklessly razed in keeping with the Gréber vision.

Much of the wisdom of 1950s-style urban planning looks like folly in retrospect. Perhaps it’s time to take the knife to the root of an institution whose entire raison d’être is to make Ottawa into Autowa.

great article

LikeLike